Highlights of the Senate Budget Committee’s Chairman’s Mark

On March 22, the Senate Budget Committee (SBC) released the Chairman’s Mark for the FY2020 Budget Resolution. It is remarkable in that, unlike many recent budget plans from Congress or the administration, it has a nodding acquaintance with reality. It does not assume rosy economic growth, but rather hews to the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) economic forecast. It does not purport to balance in 10 years, a task that is increasingly a flight of fancy. Rather, it acknowledges the reality of prevailing fiscal policy and attempts to restrain growing deficits through a modest mix of reduced mandatory spending and higher revenues over the next 5 years. It is exactly the right place to begin a discussion of how to realistically improve the budgetary outlook in the near term.

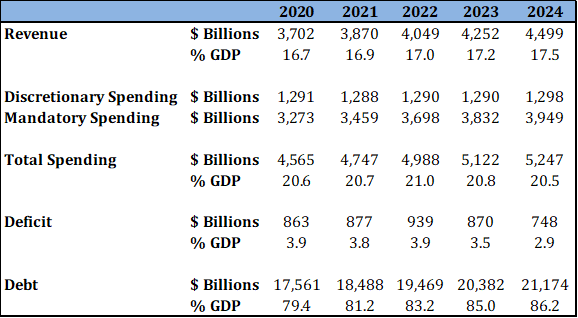

Figure 1: Chairman’s Mark Budgetary Levels

The Chairman’s Mark assumes modest revenue increases and outlay reductions that would reduce the trajectory of projected deficits to below 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of the 5-year budget window and without reaching $1 trillion as projected under current law.

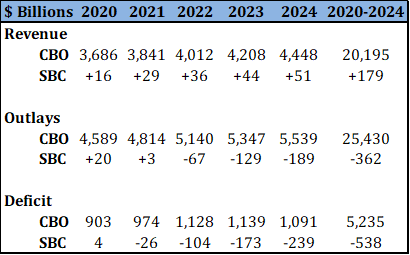

Figure 2: Chairman’s Mark Policies Compared to CBO Baseline[1]

Revenues: By the end of the 5-year budget window, revenues will amount to 17.5 percent of GDP. This is slightly above the 17.4 percent historical average. This reflects modest increases in revenue amounting to $179 billion over 5 years. While a budget resolution can’t alter federal law, the revenue increase is assumed under the Chairman’s Mark to be derived in part from improvements to the Highway Trust Fund’s financing.

Spending: By the end of the budget window, the Chairman’s Mark assumes overall federal spending declines to 20.5 percent of GDP, just above the historical average of 20.3 percent. This reflects net spending reductions of $362 billion over the next 5 years. This spending reduction is net of $213 billion in higher assumed discretionary spending, which is largely a function of irregular spending assumed in the CBO’s baseline and future defense funding increases upon the expiration of the Budget Control Act’s discretionary spending caps. The Chairman’s Mark does not assume increases to Overseas Contingency Operations above the CBO baseline. The Chairman’s Mark assumes $551 billion in savings to mandatory spending over the next 5 years. To provide for these savings, the Chairman’s Mark includes reconciliation instructions to five Senate committees to reduce the deficit over the next 5 years by at least $94 billion. The Chairman’s Mark further assumes $14 billion in debt service savings.

Deficits: Under current law, budgets deficits will grow substantially over the budget window, reaching over $1 trillion in 2022. Through higher revenues, reduced growth in mandatory spending and savings on debt service, the Chairman’s Mark assumes net deficit reduction through policy changes of $538 billion.

Additional Features: The Chairman’s Mark is a 5-year budget, departing from the prevailing practice of using 10-year budget windows. There are advantages and disadvantages to both approaches. Where a 10-year budget provides a longer planning horizon, the uncertainty and inaccuracy that necessarily attends to such long-term forecasts diminishes the value of out-year projections. The Chairman’s Mark contemplates a 2-year budget deal, providing for increases to both defense and non-defense discretionary spending levels, assuming those increases are offset over a 10-year period.

[1] Note that the CBO baseline assumes certain temporary spending provisions persist under current law, which artificially increases spending under the baseline. The Chairman’s Mark assumes these spending levels decline, but does not “count” the decline in this assumed spending as a policy change.

By: Gordon Gray

Source: American Action Forum

Next Article Previous Article